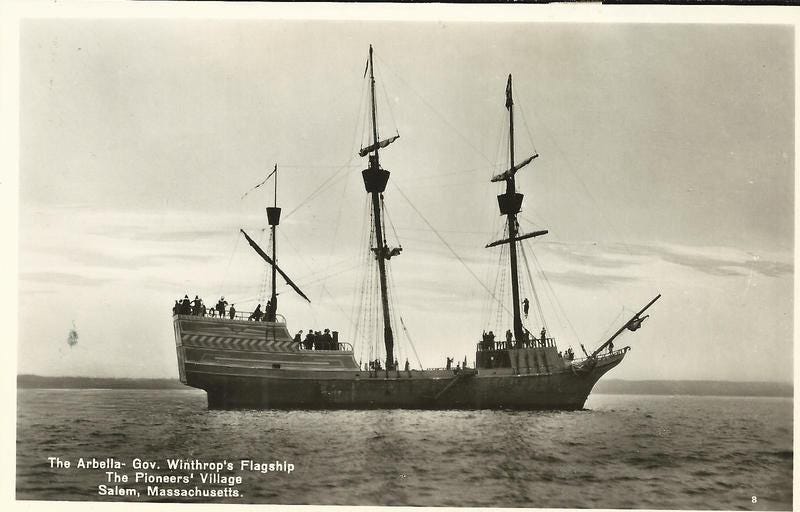

On the hopeful spring morning of April 8th, 1630, John Winthrop delivered a sermon aboard the Arbella, a ship carrying a group of anxious immigrants to Massachusetts Bay Colony. They were a mixed group of English Separatists, adventurers, treasure-seekers, and others with plenty of grit but no prospects in the Old World. The colony – founded only a decade earlier – was on the verge of a small population explosion: the Great Migration fleeing the persecutions of England’s Archbishop Laud. Winthrop admonished his listeners to regard their safe deliverance by God to the New World, after a perilous Atlantic voyage, as evidence of His fulfillment of a covenant with them and of their obligation to honor their part of the deal. Winthrop, who would lead the colony on and off for decades, wanted Massachusetts Bay to be “a city upon a hill,” a beacon to others of what a good, godly community could be, one with “the eyes of all people upon us.” Winthrop’s gleaming hilltop city is one of the earliest examples of what historians refer to as “American exceptionalism,” the notion that our nation occupies a special place in an unfolding providential mission or, for others, a grand experiment in human society. Echoes of this idea are in our founding documents, in Lincoln’s soaring rhetoric, and throughout American history. It manifests itself in ways that are cause for great pride and celebration, and in ways that are clearly not.

American leaders of all political persuasions proclaim the city upon a hill as an article of secular faith, though often in partisan ways that Winthrop would likely have regretted. His was an inclusive message pronouncing the core values of a Christian community in the New World. Ronald Reagan, in particular, liked to use the phrase, as he famously did on the night before election day in 1980 and again in his farewell address in 1989. He described his vision of the city:

But in my mind, it was a tall proud city built on rocks stronger than oceans, windswept, God blessed, and teeming with people of all kinds living in harmony and peace – a city with free ports that hummed with commerce and creativity, and if there had to be city walls, the walls had doors, and the doors were open to anyone with the will and the heart to get here.

Winthrop might have objected to the notion of a “tall proud city,” as he called for humility in being elected to participate in a providential event. Similarly, Reagan’s linking of Winthrop’s words with “free ports that hummed with commerce and creativity” secularizes and papers over their true meaning. The phrase, of course, originates in the Sermon on the Mount: “Ye are the light of the world. A city that is set upon an hill cannot be hid. Neither do men light a candle, and put it under a bushel, but on a candlestick; and it giveth light unto all that are in the house” (Matthew, 5:14-15, KJV). The next verse is equally important, and Winthrop’s listeners would have known this: “Let your light shine so before men, that they may see your good works, and glorify your Father which is in heaven” (Matthew, 5:16). Jesus’s message is a simple one; the multitudes on the mountain are blessed, they are God’s chosen people, but there are expectations to be fulfilled. They must reconcile with each other, forgive each other, love each other. The covenant will not be fulfilled till they have “paid the uttermost farthing.” There are, of course, embedded in the phrase allusions to God’s Old Testament covenant with Abraham, Issac, and Jacob and the Exodus from Egypt. Modern references to the “city upon a hill” generally ignore the burden these covenants place on us. As is true with so much of history, it is often only superficially appreciated, a gloss applied to narrow purposes.

Winthrop’s “A Model of Christian Charity,” the name by which the sermon is known, is about much more than staking a claim to being among God’s elect or a description of a nation that rises above all others. It is also a call for selflessness and shared sacrifice, a commitment to community, and above all for a unity of purpose in building the city upon a hill. As Calvinists, Winthrop understood the settlement of New England as part of an unknowable, unfolding divine plan. Their charge was to accept and determine their role in that plan. Mindful of their covenant with God, Winthrop asserted a coincidental and connected covenant that bound them to each other. Their willingness to unite their fates together as one would sustain them and shine a cleansing light back on the world they left behind. That world, for the Puritans, was an old world, a corrupt, degenerate, Godless world of rigid hierarchies and intolerance where the powerful exploited the powerless. God had delivered them safely to their new home and it was up to them to make it work. Though clear in its major articles, the contract was vague in the specifics; the travelers were free to draw up their own laws and organize their community as they best saw fit, so long as they were in accordance with God’s expectations of them – which Winthrop carefully outlined. Recreating old England in New England would not do. Breaking the covenant would cause God to withdraw His support from them and lead inevitably to their “shipwreck,” an apt metaphor given the dangerous Atlantic crossing they had just experienced.

For Winthrop, the way forward was clear. They were “to do justly, to love mercy, to walk humbly with our God.” Winthrop was a savvy judge of human nature, as only a Calvinist could be. He believed that overcoming our Hobbesian inclinations would require a renewed communitarian ethos:

. . . we must be knit together in this work as one man. We must entertain each other in brotherly affection. We must be willing to abridge ourselves of our superfluities [luxuries], for the supply of other’s necessities. We must uphold a familiar commerce together in all meekness, gentleness, patience and liberality. We must delight in each other; make other’s conditions our own; rejoice together, mourn together, labor and suffer together, always having before our eyes our commission and community in the work, as members of the same body . . .

No historian would argue that all of the men, women, and children who stepped off the Arbella, nor all those who came after them, fulfilled this covenant. His was not a perfect society. It was intolerant of outsiders and dissenters, practiced and profited from the slavery, and made merciless war on the Pequots and other Native Americans of New England. They could, and did, turn on one another on occasion. Readers today might protest that Winthrop’s words are at odds with the mythos of the rugged individual in American history. But as these weary pilgrims first felt the solid ground of an alien shore underneath their feet, they must have known that they needed each other. This was reflected in the layout of their towns, the organization of their laws and politics, and their relationships with one another. It was one of the reasons they thrived early on, unlike their southern cousins on the Chesapeake Bay. In their minds fulfilling the covenant was what mattered most, and it united them and drove them forward, at least for a time.

Winthrop’s words, now as then, challenge us. Almost from the outset, there were those who rejected the covenant in favor of their own self-interest. We do not today live in the city upon a hill. It remains an elusive ideal, always the promise of America, not the reality of America. While our covenant with one another may be strained, we cannot accept that it is broken or that it cannot be fulfilled. Our wealth, our power, and our remarkable potential as a diverse people of many gifts still make the shining city upon a hill a possibility. Our values, our full national story, and the place we occupy in human history can make us, if not as Lincoln said, “the last best hope of Earth,” then surely a force for hope at home and abroad. We can delight and rejoice in one another, mourn, labor, and suffer together, and make the conditions of others our own. Amidst the storm-tossed seas of a fractious society beset by a terrible pandemic and a calamitous economic crisis, from which no one is truly safe or truly exceptional, Winthrop reminds us that our deliverance will not come from turning against one another, but by turning toward one another.